The Phillips Curve, which posits an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation, has historically been used to argue that wage increases (as a result of lower unemployment) lead to inflation.

Yet, this relationship has been increasingly questioned. During the 1970s, for example, many economies experienced stagflation—high inflation coupled with high unemployment—challenging the validity of the Phillips Curve. More recently, despite low unemployment rates in many advanced economies post-2008, inflation has remained subdued.

As the debate between the Federal Government and the Labour Union over the actual amount to be paid as the minimum wage intensifies, a common misconception persists: that increasing wages will inevitably worsen Nigeria’s inflation woes.

Read also: Labour declares indefinite strike from June 3 over minimum wage talks

Currently, Nigeria has experienced inflation hikes for 16 consecutive months, with the rate rising from 33.20 percent in March to 33.69 percent in April 2024.

This belief, however, oversimplifies a complex economic relationship that exists between wages and inflation. While wage increases can influence inflation, they are not the sole or even primary driver. When wages rise, it generally heralds good news for workers, indicating improved living standards and increased purchasing power.

This uptick in income can boost consumer spending, contributing to economic growth. However, the relationship between wage increases and inflation is a topic rife with misconceptions. The simplistic notion that higher wages inevitably lead to inflation ignores the complex interplay of various economic factors.

In the same vein, an increase in these labour wages will then make businesses face higher labour costs—a fractional part of input costs—and often pass these costs onto consumers in the form of higher prices for goods and services. This upward pressure on prices contributes to inflationary trends within the economy but is not automatic.

Moreover, wage increases can stimulate demand for goods and services, leading to higher levels of consumer spending. While this initially boosts economic activity, it can also strain the supply side of the economy, potentially leading to shortages and price increases.

Read also: Minimum wage negotiation deadlocked, as labour walks out again

Additionally, wage hikes can fuel expectations of future inflation among consumers and businesses. This expectation can become a self-fulfilling prophecy as firms anticipate higher costs and adjust their pricing accordingly, further exacerbating inflationary pressures.

“While wage increases can influence inflation, they are not the sole or even primary driver. When wages rise, it generally heralds good news for workers, indicating improved living standards and increased purchasing power.”

The relationship between wage increases and inflation is not deterministic and can vary depending on a range of factors, including the state of the economy, monetary policy, productivity levels, competitive market, exchange rate, supply chain disruption, and global economic conditions.

One major oversight in the wage-inflation myth is the role of productivity. When wage increases are matched by productivity gains, businesses can afford to pay higher wages without raising prices. Increased productivity means more output per hour worked, which offsets higher labour costs.

Market structures also significantly influence inflation. In competitive markets, businesses have limited ability to pass on higher wage costs to consumers. Instead, they might reduce profit margins, improve efficiency, or innovate to stay competitive.

Retail giants like Walmart and Amazon have successfully raised wages without significant price hikes. Through economies of scale, supply chain efficiencies, and technological advancements, these companies have shown that higher wages do not necessarily lead to higher prices.

Developing nations experiences

The relationship between wage increases and inflation is not uniform across all economies. In developing nations, this dynamic can vary significantly based on several factors, including economic structure, policy environment, and external influences.

Brazil

In Brazil, the government implemented significant minimum wage increases in the early 2000s. Despite concerns, inflation did not spike proportionally. Instead, productivity improvements in various sectors helped absorb higher labour costs.

The agricultural sector, in particular, saw technological advancements that boosted productivity and kept food prices stable. The United States Department of Agriculture shows that Brazil has led the world in agricultural productivity since the beginning of the 2000s, among the 187 countries surveyed.

Brazilian agricultural productivity increased by an average of 3.18 percent per year until 2019. This performance can be attributed to the Brazilian government’s efforts associated with reforms in the financing system, pricing policy, subsidy cuts, and rural insurance, which helped counterbalance wage growth.

In addition, investments in research and the adoption of low-carbon agricultural practices have also contributed to productivity gains, making Brazil even more prominent in the agricultural scenario.

China

China’s rapid economic growth over the past few decades has been accompanied by substantial wage increases. However, inflation has been kept in check largely due to massive productivity gains. Between 2000 and 2015, labour productivity in China increased by an average of 9.6 percent per year, significantly outpacing wage growth.

This remarkable productivity growth is the result of significant investments in technology and infrastructure. China’s focus on high-tech industries, such as electronics and automotive manufacturing, has led to substantial productivity gains.

For example, the Chinese electronics industry saw an average annual productivity growth of 10.2 percent between 2000 and 2015. These advancements have allowed businesses to pay higher wages without raising prices.

China’s emphasis on education and skill development has also been a crucial factor. The expansion of higher education and vocational training programmes has created a skilled workforce capable of supporting high-productivity industries.

By 2018, China had the largest number of STEM graduates globally, providing a steady supply of skilled labour to its growing industries.

Moreover, strong regulatory frameworks and competitive markets have mitigated inflationary pressures. The Chinese government has implemented policies to ensure fair competition and prevent monopolistic practices, keeping prices stable.

Additionally, China’s large domestic market and export-oriented economy have created competitive pressures that discourage price increases.

The significant productivity gains in China have enabled businesses to absorb higher labour costs without passing them onto consumers. This has helped maintain low inflation despite substantial wage increases.

For instance, in the automotive sector, productivity improvements through automation and process optimisation have offset the impact of rising wages, allowing companies to remain competitive without increasing prices.

India

In India, the relationship between wage increases and inflation has been more complex. While wage hikes in the formal sector have sometimes led to higher prices, especially in urban areas, the impact on overall inflation has been moderated by productivity gains in the services and IT sectors.

Rural wage increases, driven by schemes like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), have had a limited impact on inflation due to increased agricultural productivity and rural development initiatives. From 2005 to 2015, productivity in India’s IT sector grew by 8.5 percent annually, helping to balance wage growth in the sector.

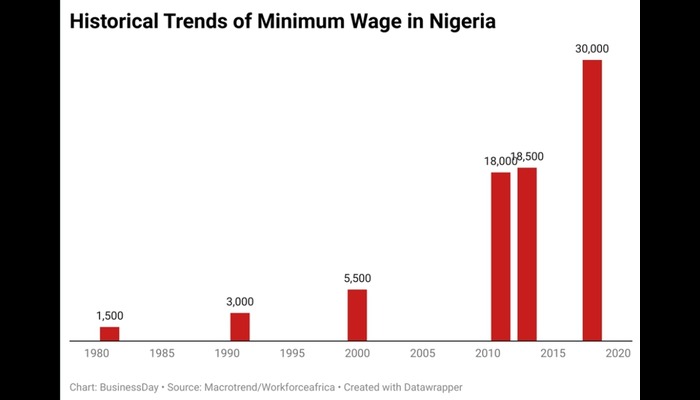

Over the years, Nigeria’s minimum wage has seen substantial increments aimed at improving the standard of living for its workers. However, these increases have not always aligned seamlessly with inflation trends, highlighting the complex interplay between wage policies and economic realities.

In 1981, the minimum wage was set at ₦1,500, with an inflation rate soaring to 20.81 percent. This period was marked by economic instability and high inflation, significantly eroding the purchasing power of workers despite the wage levels.

By 1991, the minimum wage had doubled to ₦3,000. Interestingly, inflation had decreased to 13.01 percent, suggesting some economic stabilisation. However, the persistent double-digit inflation rate continued to undermine real income gains for the workforce.

The year 2000 saw the minimum wage rise to ₦5,500, while inflation dropped further to 6.93 percent. This period reflects a rare instance where wage increases outpaced inflation, potentially providing some relief to Nigerian workers.

Significant wage hikes occurred in the following decade. In 2011, the minimum wage was ₦18,000, with inflation at 10.83 percent. By 2013, wages had slightly increased to ₦18,500, and inflation had decreased to 8.5 percent, indicating a relatively balanced economic environment.

The latest significant jump was in 2018, with the minimum wage set at ₦30,000. During this time, inflation was recorded at 12.1 percent, reflecting a slight resurgence in inflationary pressures despite the substantial wage increase.

These data points underscore that while wage hikes are crucial for improving living standards, they must be carefully managed alongside measures to control inflation, ensuring that real incomes are genuinely enhanced.